Module Print Version

Table of Contents

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 The Atmosphere

- 2.1 Structure

- 2.1.1 Troposphere

- 2.2 Composition

- 2.2.1 Water Vapor

- 2.2.2 Vapor Distribution

- 2.3 Variability

- 2.4 Weather & Fire

- 3.0 Pressure

- 3.1 Units

- 3.2 Variation

- 3.3 Altitude

- 3.4 Exercise

- 4.0 Heat

- 4.1 Energy from Sun

- 4.2 Heat balance

- 4.3 Exercise

- 5.0 Temperature

- 5.1 Influencing Factors

- 5.2 Seasons

- 5.3 Solar Duration

- 5.4 Pollution

- 5.5 Cloud cover

- 5.5.1 Exercise

- 5.6 Surface Properties

- 5.6.1 Albedo

- 5.6.2 Transparency

- 5.6.3 Conductivity

- 5.6.4 Specific Heat

- 5.7 Evaporation

- 5.8 Condensation

- 6.0 Radiation

- 6.1 Radiation Balance

- 6.2 Temperature Lag

- 6.2.1 Seasonal

- 6.2.2 Daily

- 6.3 Exercise 1

- 6.4 Exercise 2

- 7.0 Tying it Together

- 7.1 Importance

- 7.2 Watch Out

- 8.0 Summary

1.0 Introduction

This module provides background information on the basic weather processes affecting wildland fire behavior. It is part of the S-290 Intermediate Wildland Fire Behavior course and provides an introduction to topics that are discussed in greater detail in other course modules.

At the end of this module, you should be able to:

- describe the structure and composition of the atmosphere,

- define weather and list its elements,

- describe the Sun-Earth radiation budget and Earth’s heat balance,

- describe factors affecting the temperature of Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere,

- describe the greenhouse effect and its influence on air temperature, and

- describe temperature lag and how daily and seasonal temperature lags affect wildland fire behavior.

2.0 The Atmosphere

The atmosphere is a layer of gases—mainly nitrogen and oxygen—that surrounds Earth. Compared to the ~8000-mile diameter of Earth, the atmosphere is very thin. Approximately 99 percent of all atmospheric gases lie within 18 miles of Earth’s surface. Yet this thin layer provides us with the air we breathe, shields the planet from potentially destructive meteors or other space debris, protects us from ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, and stores heat energy that makes the planet habitable for humans and other life.

2.1 Structure

The atmosphere is divided into layers based on the change in temperature with altitude.

In order of increasing height, these layers are the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere.

The tropopause marks the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere, while the stratopause separates the stratosphere from the mesosphere. The boundary between the mesosphere and thermosphere is called the mesopause.

Question:

In which layers of the atmosphere does “weather” affecting fires occur? (select all that apply)

- the mesosphere

- the thermosphere

- the stratosphere

- the troposphere

Feedback:

Answer "d." is correct. Almost all of Earth’s weather occurs in the troposphere, the layer closest to the surface.

2.1.1 Troposphere

Temperature tends to decrease with altitude through the troposphere, which is the layer where weather processes occur. The troposphere extends from the surface to between 6 and 12 miles above sea level. The top of the troposphere is marked by the tropopause, which separates the troposphere from the stratosphere. The height of the tropopause tends to be highest over the tropics and lowest over the polar regions. It marks the position of high winds called the jet stream, which meanders in narrow channels from west to east across both the northern and southern hemispheres. The tropopause also represents the upper limit of nearly all weather in the atmosphere.

2.2 Composition

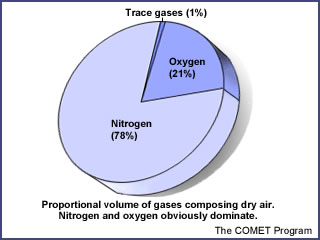

Nearly 75% of the atmosphere is contained in the troposphere. Nitrogen occupies 78% of the total dry gas volume and oxygen accounts for 21%. The remaining 1% of the volume includes argon, neon, helium, hydrogen, xenon, and carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide with its significant greenhouse properties represents only a fraction of a percent of the gases comprising Earth’s atmosphere.

2.2.1 Water Vapor

Additionally, the atmosphere contains water vapor, an extremely important constituent contributing to water and ice clouds that produce various types of precipitation. Water vapor also stores and releases great quantities of heat energy, called latent heat, that is used to power thunderstorms and hurricanes.

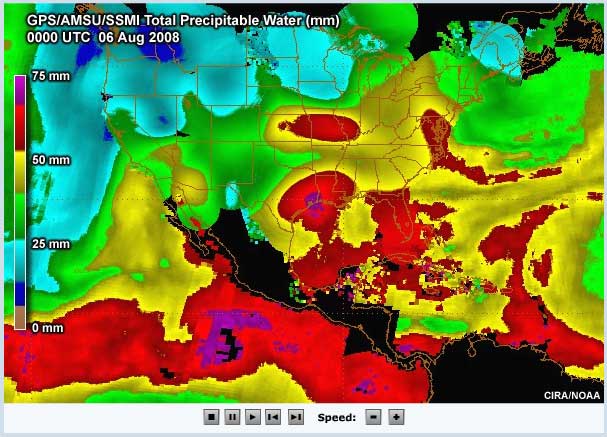

In this image, the red and gold colors indicate the highest atmospheric water vapor amounts. Over the southwestern U.S., water vapor is being carried northward by the North American monsoon. Moisture associated with tropical storm Edouard can be observed spreading across Texas.

2.2.2 Vapor Distribution

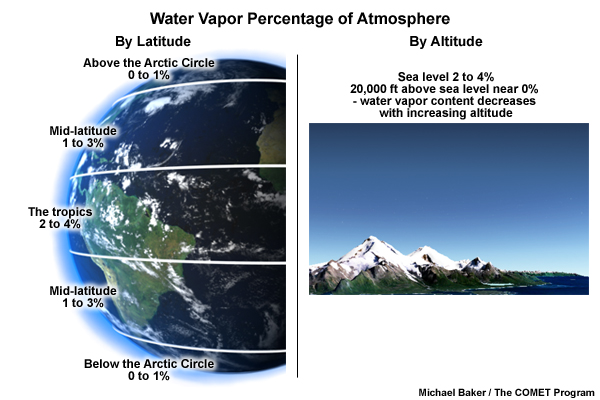

Almost half of all water vapor is found within the lowest three miles of the atmosphere, where amounts vary with region, elevation, and season.

Question: For which regions, shown in the series of images at the right, would you expect the highest and lowest water vapor amounts? Feedback: The highest water vapor amounts are typically found in tropical locations, where water vapor can account for up to 4% of atmospheric gases. In colder, polar regions, its concentration might be a mere fraction of a percent. Water vapor amount decreases with altitude so mountains and higher elevations have lower water vapor amounts than prairie or coastal areas. The images are arranged from top to bottom in order from highest to lowest water vapor amounts. |

|

Highest |

Lowest

|

2.3 Variability

Weather is the short-term variation of the atmosphere. It includes changes in

- air pressure,

- air temperature,

- humidity,

- wind,

- clouds,

- precipitation, and

- visibility.

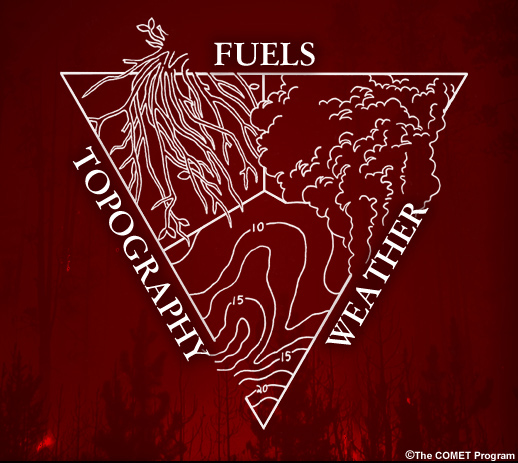

2.4 Weather & Fire

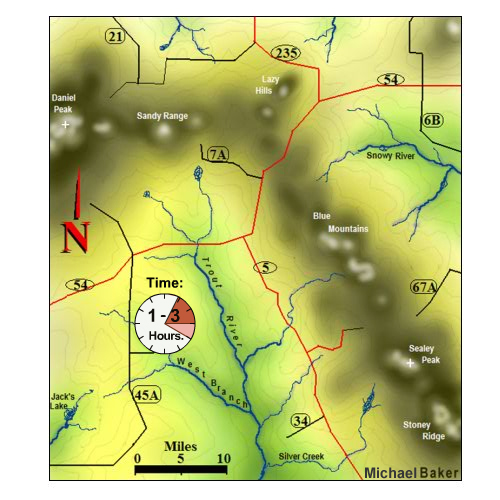

Three environmental factors—weather, topography, and fuels—strongly influence wildland fire behavior. Of these, weather is the most variable over space and time. Because of its variability, weather can be difficult to predict, particularly at small scales and over longer time periods.

3.0 Pressure

The first element of weather we will examine is pressure.

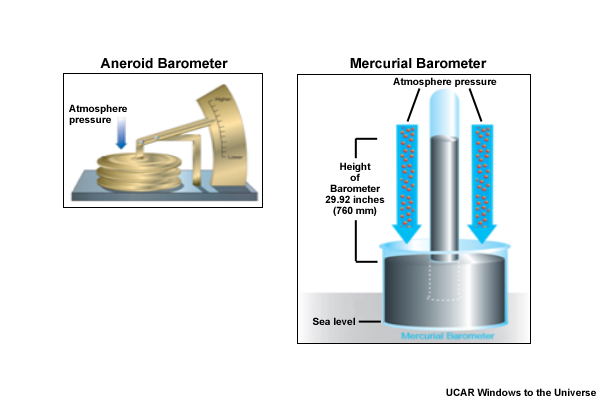

Atmospheric pressure, or air pressure, is defined as the amount of force exerted by the weight of air molecules on a surface. This downward force or weight is typically measured in millibars or in inches of mercury. It results from the pull of gravity on the atmosphere. Pressure differences cause winds and can signal the passage of a front.

3.1 Units

The most common pressure unit used on surface and upper level weather maps is the millibar (mb). Pressure is also measured in inches of mercury (in Hg). At mean sea level, the average pressure is 1013.25 mb or 29.92 in Hg. This pressure, referred to as the standard atmospheric pressure, can also be expressed as 14.7 pounds per square inch. The standard atmospheric pressure is essentially the weight of a column of air with a cross section of 1 square inch, extending from mean sea level to the top of the atmosphere.

In the past, pressure was measured directly using mercury barometer. Most current measurements come from an aneroid barometer, a calibrated weather instrument that estimates the weight of the atmosphere on a surface.

3.2 Variation

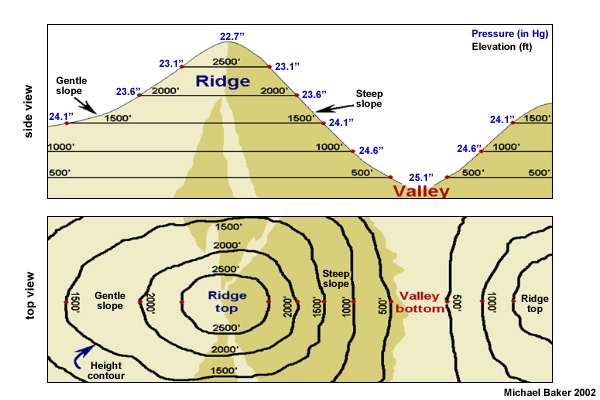

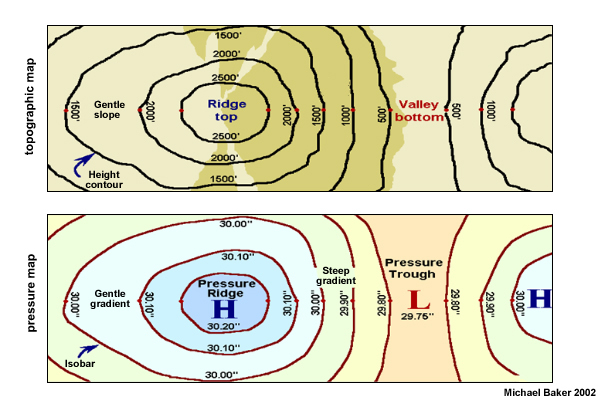

Pressure varies with both time and location as air masses move across the continent. Pressure differences in the atmosphere can be thought of similarly to elevation changes over an area of terrain.

Just as contours delineate elevations and mark ridges and valleys on a topographic map, lines of constant pressure, called isobars, can create a view of the high pressure ridges and low pressure troughs existing in the atmosphere. As with contours on topographic maps, the tighter these lines, the stronger (or steeper) the gradient.

Pressure differences across an area drive winds, with stronger pressure gradients resulting in higher wind speeds.

3.3 Altitude

Atmospheric pressure decreases with increasing altitude because as one moves higher, there is simply less air overhead. This decrease in air pressure is quite rapid through the troposphere.

Observe that about half of the atmosphere’s weight is concentrated within the lowest 3 1/2 miles of the troposphere. At 3 1/2 miles or 18,000 feet above sea level, atmospheric pressure is approximately 500 millibars or 15 inches mercury.

In the lowest 10,000 feet of the atmosphere, atmospheric pressure decreases, on average, approximately 1 inch mercury for every 1000-foot increase in elevation.

3.4 Exercise

Refer to the image below to complete these statements. (choose from answer optons in [brackets])

Question 1:

Nearly half the weight or mass of the atmosphere is located below [1000 ft, 12,000 ft, 18,000 ft].

Feedback 1:

Nearly half the weight or mass of the atmosphere is located below 18,000 feet or 3 1/2 miles.

Question 2:

Standard atmospheric pressure is the [average, instantaneous] weight of a column of air extending from [the surface, sea level] to the [tropopause, top of the atmosphere].

Feedback 2:

Standard atmospheric pressure is the average weight of a column of air extending from sea level to the top of the atmosphere.

Question 3:

Below 10,000 feet, for every 1000-foot increase in elevation, air pressure [increases, decreases] approximately [1 in Hg, 2 in Hg, 3 in Hg].

Feedback 3:

Below 10,000 feet, for every 1000-foot increase in elevation, air pressure decreases approximately 1 in Hg.

4.0 Heat

The Sun drives our weather. It is the principal source of light and heat energy for Earth and its atmosphere and directly affects temperatures on Earth.

On a much smaller scale, heat also originates from large fires, and from other natural and human-related energy-release processes.

4.1 Energy from Sun

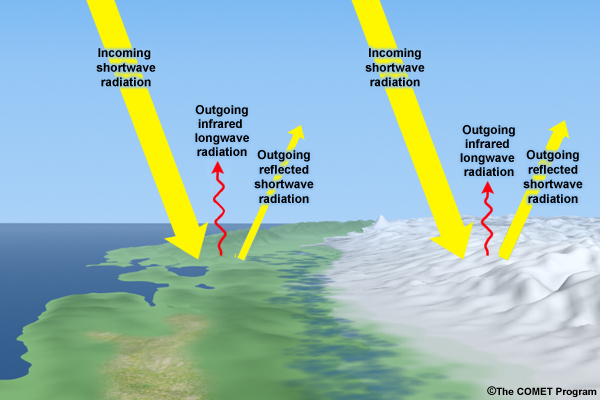

Energy from the Sun reaches Earth’s atmosphere in the form of shortwave solar radiation. Most of this solar radiation travels through the atmosphere and reaches Earth’s surface. Much of the radiation is absorbed, but a portion of the solar radiation is reflected back to space. As Earth's surface absorbs radiation and warms, heat is radiated to the atmosphere as terrestrial or longwave radiation.

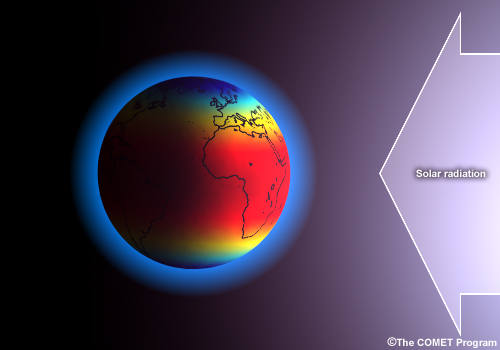

4.2 Heat Balance

For the globe as a whole, there is a balance between the amount of solar energy reaching Earth’s surface and the amount of terrestrial radiation returning to space. However, because not all regions of Earth’s surface receive the same amount of sunlight per unit area, regional surpluses and deficits in heat produce a range of temperatures across the globe. Weather systems carry heat from the equatorial region, mixing the warmer air with colder air at higher latitudes. This heat transport and mixing helps maintain a global energy balance.

4.3 Exercise

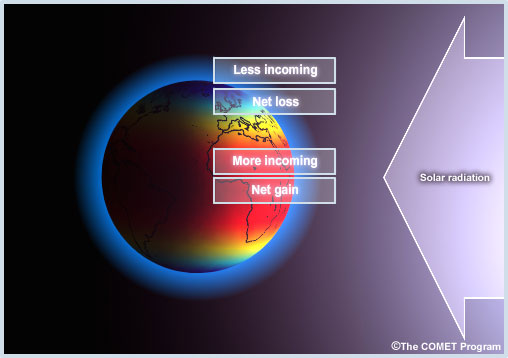

Looking at the image below, determine where you would place the labels onto the image. Two labels will appear near the Arctic and two near the tropics.

- Less incoming

- More incoming

- Net gain

- Net loss

Feedback:

Because of Earth’s curvature, energy reaching the polar regions is spread out over a larger area than the same energy reaching the lower latitudes. Less incoming solar energy at the poles results in a net loss in radiation at the surface.

5.0 Temperature

The amount of heat energy available determines temperature. Temperature can be thought of as the degree of hotness or coldness that can be measured using a thermometer. Temperature also affects the relative humidity. Essentially, warmer air will have a lower relative humidity than cooler air for the same amount of water vapor.

5.1 Influencing Factors

The temperatures of Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere are affected by:

- solar angle and duration,

- atmospheric moisture and air pollutants, and

- surface properties of the terrain and vegetation.

5.2 Seasons

Outside the equatorial region, temperatures can vary dramatically with season. Seasons are caused by the tilt of Earth’s axis. This tilt leads to variations in the amount of solar radiation received by the northern and southern hemispheres.

As Earth orbits the Sun, the hemisphere tilted toward the Sun experiences summer while the hemisphere tilted away experiences winter. The animation represents the Northern Hemisphere view of Earth's position during different seasons.5.3 Solar Duration

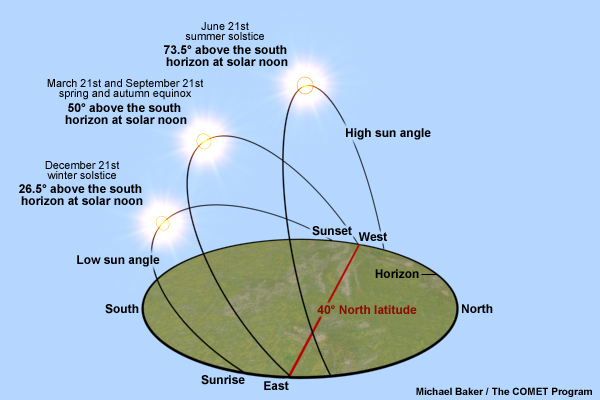

Solar angle and duration vary by latitude and with variations in the local terrain.

Changes in solar angle and the length of daylight strongly influence the amount of solar radiation striking a point on Earth’s surface. In general, the higher the solar angle and the longer the daylight, the greater the solar heating.

5.4 Pollution

Clouds, water vapor, and air pollutants absorb, reflect, and scatter solar and terrestrial radiation. Their presence and amount significantly affect the temperatures of Earth’s surface and atmosphere.

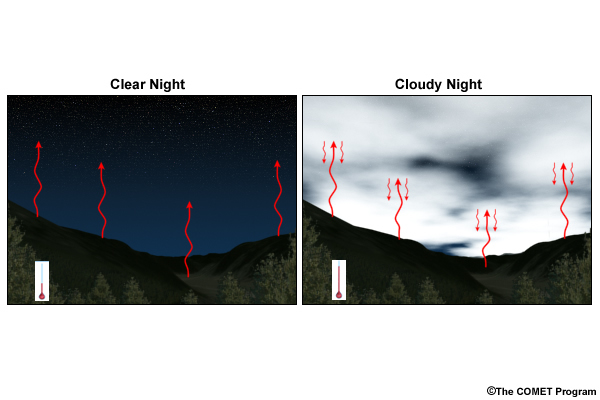

5.5 Cloud Cover

Cloud cover and high humidity significantly influence air and surface temperatures. During the day, clouds reflect incoming sunlight, preventing a portion of this heat energy from reaching Earth’s surface. Nights with cloud cover are generally warmer than nights without cloud cover because the cloud cover reduces the loss of longwave terrestrial radiation to space. The cloud cover is often compared to a blanket or insulation holding in the terrestrial heat. In reality, the radiative properties of the clouds themselves provide an additional source of nighttime heating.

The rate of heat loss or cooling depends on the amount of humidity or moisture in the air, as well as on the height of the cloud cover above the ground.

5.5.1 Exercise

Question: After sunset and in the absence of other weather-influencing events, which cloud cover amounts shown in the images at the right will allow the most heat to escape to space? Feedback: In the absence of weather events during the night, clouds prevent radiation from escaping to space. The more cloud cover, and the lower the height of clouds, the less radiation will escape. The images are arranged from top to bottom in order from highest to lowest amount of heat escape. |

|

Most escapes |

Some escapes |

||

Less escapes |

||

Least escapes |

5.6 Surface Properties

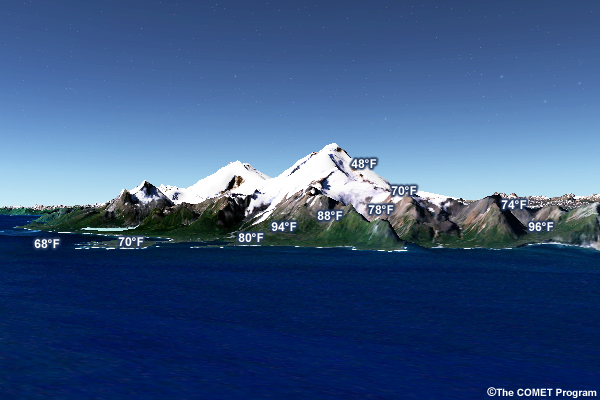

Surface properties of terrain and vegetation—including color and texture, transparency, conductivity, specific heat, evaporation, and condensation—can dramatically affect surface and air temperatures. These properties influence the amount of heat energy absorbed and reflected by the surface.

As an example, the difference in temperature between a coastal shoreline and a nearby rocky cliff can be as much as 30 degrees because of the different surface properties.

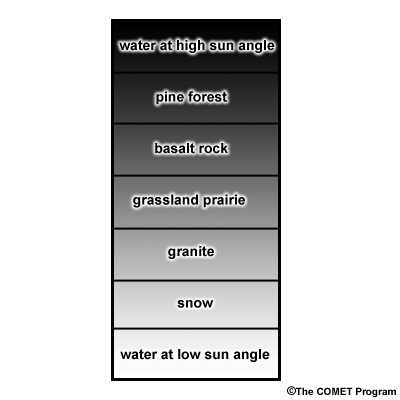

5.6.1 Albedo

The ability to reflect solar energy is referred to as albedo.

Rough textured, irregular, and dark-colored materials have a low albedo, making them good absorbers of solar radiation. Uniform and light-colored materials such as snow, water at low sun angles, and sandy soils have a higher albedo and reflect more solar radiation, thus absorbing less energy.

Question: Which surfaces, shown in the series of images at the right, will have the highest albedo values? Feedback: Albedo is highest for snow and light-colored uniform land surfaces, such as a grass field or prairie. Forests are less reflective and have a lower albedo, while a burned area, which mostly absorbs radiation, has the lowest albedo. The images are arranged from top to bottom in order from highest to lowest albedo. |

|

Highest albedo |

|

||

|

||

Lowest albedo |

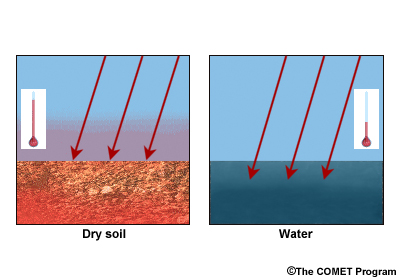

5.6.2 Transparency

Transparency affects the distribution of heat and light through a substance. Water is highly transparent and allows solar radiation to travel to a greater depth. The water’s surface and the air just above the surface are therefore able to remain cooler. Soil is much less transparent and concentrates heat within the topmost layer, resulting in a higher surface temperature.

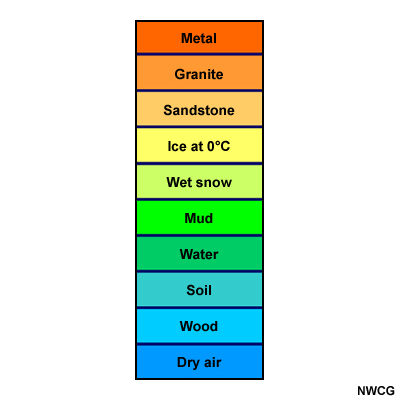

5.6.3 Conductivity

Conductivity refers to the ability of substance to transfer heat to the surrounding environment. Metal and granite are examples of good conductors, allowing efficient transfer of heat energy. Air, wood, and soil do not transfer heat energy efficiently, and are therefore good insulators.

Question: Conductivity is the ability of a substance to transfer heat energy, which can affect the temperature of the surrounding environment. Which landscapes, depicted by the images at the right, have the highest heat transfer ability? Feedback: Rocks have a high conductivity and water has a moderate conductivity. A burnt forest with high soil exposure will have a slightly higher conductivity than a live fuel setting. The images are arranged from top to bottom in order from highest to lowest conductivity. |

|

Highest conductivity |

|

||

|

||

Lowest conductivity |

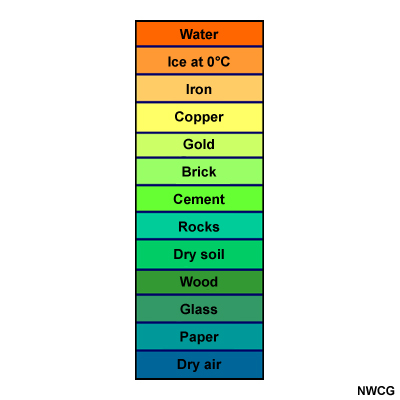

5.6.4 Specific Heat

Specific heat is the capacity of a substance to absorb and store heat energy. Different land surfaces have different specific heat capacities, which can affect air and surface temperatures. The specific heat of water is five times that of rock, meaning that water has the capacity to store more heat energy for more time. The high specific heat of water moderates temperature changes over land areas adjacent to lakes or coastlines.

The specific heat of air near the surface can vary substantially from one region to another, depending largely on the amount of moisture present.

Question: Specific heat is the ability to store heat energy and can affect surface and air temperatures. Each of the regions shown on the right has a different specific heat based on the characteristics affecting the lowermost atmosphere. Which images depict the landscapes with the highest heat storage capacities? Feedback: Because of the greater amount of water vapor in the air, tropical and coastal regions have a higher specific heat capacity than desert, cured vegetative, high mountain, and arctic regions. The images are arranged from top to bottom in order from highest to lowest specific heat. |

|

Highest Specific Heat Capacity |

|

||

|

||

Lowest Specific Heat Capacity |

5.7 Evaporation

Changes of water from liquid to gas or gas to liquid greatly affect the heating and cooling of the atmosphere. Evaporation is the phase change of water from a liquid to a gas. Evaporating water removes heat from the environment and is therefore a COOLING process in the atmosphere. The coolness you feel on your skin after stepping out of a shower or swimming pool is an example of the heat loss resulting from evaporation.

Evaporation adds moisture to the atmosphere. If enough moisture is added to the atmosphere by evaporation, dew, fog, clouds, and precipitation can form.

5.8 Condensation

Condensation is the phase change of water from a gas to a liquid. Condensation of water adds heat energy to the environment and is thus a WARMING process in the atmosphere. As an example of this heat release process, consider what happens if your skin comes into contact with steam. The heat released as the vapor condenses to liquid on your skin can intensify the resulting burn.

The heat released in the condensation process is referred to as latent heat. As this heat is released, it helps storms, including thunderstorms and hurricanes, to form and grow.

6.0 Radiation

The additional heat provided by the atmosphere's ability to absorb outgoing longwave radiation is referred to as the greenhouse effect. Heat is absorbed by greenhouse gases, including water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide.

These greenhouse gases radiate energy and act to moderate Earth’s temperature. Without their absorption abilities, Earth’s radiant heat would escape to space and the planet would be much cooler.

The term “greenhouse effect” has been used for over a century, but it is not a correct analogy. A greenhouse suppresses mixing of the air warmed in the greenhouse with the surrounding atmosphere. In reality, the atmosphere becomes an additional source of heating because of the radiation absorbed by the greenhouse gases.

6.1 Radiation Balance

During some months of the year and some hours of the day, the incoming energy from the Sun exceeds the outgoing energy of Earth. While this excess occurs, the temperature continues to rise.

The highest temperature occurs when the incoming energy no longer exceeds the outgoing energy. After that, there will be a net loss of energy and temperatures cool until the incoming solar energy again exceeds Earth’s outgoing energy.

6.2 Temperature Lag

The warmest and coldest times of the day and the year rarely coincide with the times of maximum and minimum incoming solar radiation, referred to as insolation.

Remember that temperature depends on the balance between incoming and outgoing radiation. When the incoming radiation or insolation is larger than the outgoing radiation, there is a net radiation gain and temperatures will rise. Temperatures cool when the outgoing radiation exceeds the incoming radiation resulting in a net radiation loss. Because of this balance, the maximum temperature occurs after the peak insolation for the day or year. Likewise, the minimum temperature occurs later than the minimum insolation.

The difference in time between the maximum insolation and maximum temperature and between the minimum insolation and minimum temperature is referred to as the temperature lag.

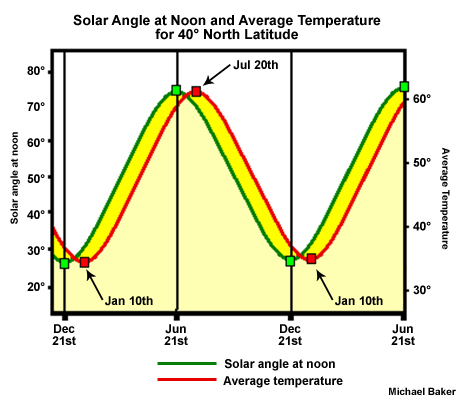

6.2.1 Seasonal

The highest temperatures during the year occur, on average, 3 to 5 weeks after the maximum solar intensity (highest solar angle), which occurs around June 21, or the summer solstice in the northern hemisphere.

The lowest temperatures occur, on average, 3 to 5 weeks after the minimum solar intensity (lowest solar angle), which occurs around December 21, or the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere.

A variety of factors affect the timing of the peak fire season in an area. For instance, solar radiation is most intense in June and July, when solar angles are at their highest and daylight is at its longest. However, the highest temperatures and lowest relative humidities are often observed in late July and August.

6.2.2 Daily

Lags also occur in daily temperatures. During the summer, minimum daily temperatures typically occur shortly after sunrise.

For several hours after sunrise, the air near the ground is usually slow to warm and relative humidity remains high because of the slow response of the atmosphere to heating. Cloud cover can further extend this morning temperature lag, often by several hours.

The time lag between solar noon—when the solar angle is the highest—and the maximum daily temperature is typically on the order of a few hours. Along coasts or in humid areas, this lag might be around 2 hours, while in drier areas the maximum daily temperatures occur roughly 4 to 6 hours after solar noon.

6.3 Exercise 1

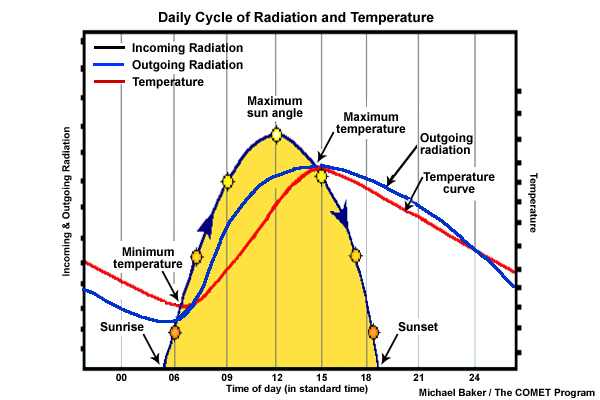

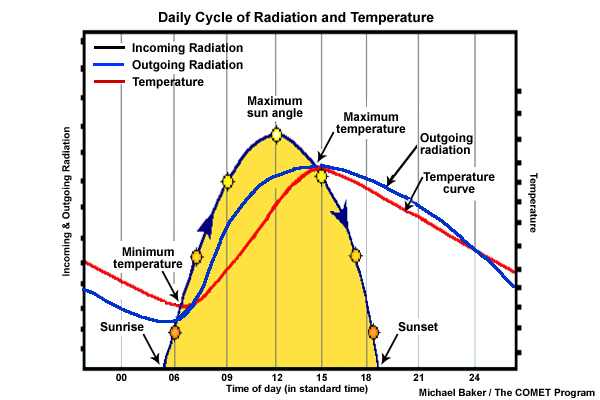

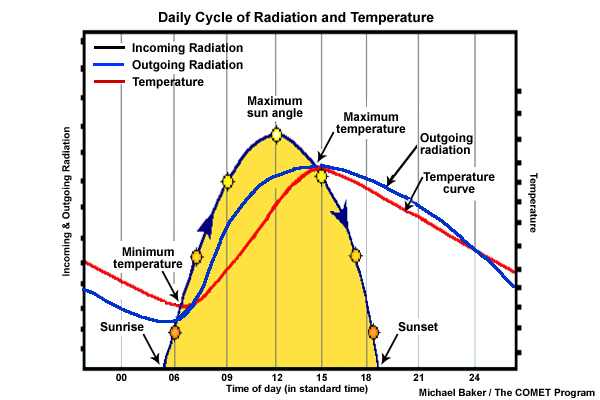

The graphic illustrates incoming radiation, outgoing radiation, and corresponding temperatures as a function of time of day.

The black curve represents incoming solar radiation. The blue curve represents outgoing terrestrial radiation. The red curve indicates the corresponding air temperature, which is governed by the balance between incoming and outgoing energy.

Question 1:

Referring to the "Solar Angle and Intensity and Average Temperature" image above, at 0800 hours, which is larger?

- incoming radiation

- outgoing radiation

- they are the same

Question 2:

Based on this answer, how will temperature behave if no other weather events are occurring?

- temperature will rise

- temperature will fall

- temperature is constant

Feedback for 1 & 2:

In both cases the answer is a. In the morning hours on a sunny day, incoming radiation is higher than outgoing radiation and temperatures will warm.

Question 3:

Referring again to the "Solar Angle and Intensity and Average Temperature" image above, at 1700 hours, which is larger?

- incoming radiation

- outgoing radiation

- they are the same

Question 4:

Based on this answer, how will temperature behave if no other weather events are occurring?

- temperature will rise

- temperature will fall

- temperature is constant

Feedback for 3 & 4:

In both cases the answer is b. By mid-afternoon on a sunny day, the outgoing terrestrial radiation will exceed the incoming solar radiation. Temperatures begin to cool.

6.4 Exercise 2

Question 1:

Dry climates usually have larger daily temperature ranges than more humid climates. Why?

- atmospheric pressure is lower

- less water vapor is present so the specific heat of the air is lower

- solar angle and duration are usually greater in these regions

- d. there is more vegetation to store heat energy from the Sun

Question 2:

The presence and thickness of clouds affects temperature

- only during the night

- only during the day

- during both night and day

- clouds do not affect temperature

Feedback 1 & 2:

The answers are b and c, respectively. Recall that water has a high specific heat and is therefore effective at storing heat energy.

Water in the atmosphere (e.g., clouds) also reflects incoming shortwave radiation from the Sun and helps prevent outgoing terrestrial radiation from escaping to space.

When less water vapor or less cloud cover is present, the surface tends to warm more rapidly during the day, and can also cool more quickly during the night.

7.0 Tying it Together

Weather is a critical variable influencing fire behavior, and is one side of the fire environment triangle. Of the three variables—weather, topography, and fuels—it is important to remember that weather varies most substantially with time and location and therefore must be rigorously monitored.

7.1 Importance

Basic knowledge and awareness of weather is essential for making critical fire management decisions.

According to the Standard Firefighting Orders in the NWCG Fireline Handbook, all firefighters should “keep informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts.”

Firefighters are also instructed to “know what your fire is doing at all times, observe personally and use scouts.”

7.2 Watch Out

Three weather-related concerns are included in the “Watch Out” Situations. The first involves winds changing. Wind increasing or changing direction is a critical concern for fire behavior.

The second “Watch Out” situation is when conditions are hot and dry. Hot, dry weather directly affects the status of fuels.

The third situation is being out of one’s element or unfamiliar with the weather or other local factors affecting an area. A lack of awareness of these factors influencing wildland fire behavior can quickly compound a dangerous situation.

Remember, wind shift on a hot, dry day – get out of fire’s way!

8.0 Summary

This module summarized the basic atmospheric and energy properties essential to understanding why the weather behaves as it does.

Weather elements examined include pressure and temperature.

Pressure is the weight of the atmosphere and varies with elevation.

Temperature is the amount of heat available in the atmosphere and depends on the balance of incoming solar energy and outgoing longwave radiation. Surface properties, including albedo and specific heat, affect the temperature of both the terrain and the lower atmosphere. Clouds, smoke, and pollution also affect surface and atmospheric temperatures.

Daily and seasonal temperatures tend to lag the radiation peak, with seasonal temperatures not peaking until 3 to 5 weeks following the summer solstice. Likewise, the hottest and driest conditions typically occur in the middle or late afternoon, a few hours after solar noon.

Awareness of basic weather variables and how they vary over time and space is essential for wildland firefighting efforts. Weather significantly influences the ignition, spread, and intensity of wildfires.